Shortly after writing this, reports came in that the Internet in Egypt had become a black hole, entirely–or almost entirely–inaccessible. Updates soon.

This question has been posed to me constantly over the past two days from journalists doing their best to understand the relationship between online and offline forms of protest. I feel their pain – after the mainstream media went gaga over Iran’s 2009 protests, journalists must be considerably wary when tackling this subject: Go one way, and you risk overstating the influence, go the other and you’re dismissed as assuming individuals in the Arab world incapable of leveraging social media tools for organizing.

In thinking on this, I was inspired by these words, from “technosociologist” Zeynep Tufekci, in reference to Tunisia:

To say that social-media was a key part of the revolution does not necessarily mean that people used GPS-enabled phones to coordinate demonstrations; that is simplistic and misses the point in which social media shapes the environment in general. What it means is that the people acted in a world where they had more means of expressing themselves to each other and the world, being more assured that their plight would not be buried by the deep pit of censorship, and a little more confidence that their extended families, their neighbors, their fellow citizens were similarly fed up, as poignantly expressed by the slogan taken up by the protestors: “Yezzi Fock! Enough!”

Tufekci has repeatedly (and very thoughtfully) asked why journalists and bloggers insist on differentiating so strongly between “online” and “offline” and I think she has an extremely valid point: Though Egypt and Tunisia have considerably lower Internet penetration rates than the United States, young Egyptians and Tunisians use the Internet in pretty much the same way as young Americans, albeit perhaps more politicized at times. And so it shouldn’t come as much of a surprise that, when organizing a massive protest, they might turn to Facebook to get folks to sign up.

Now, does any of this warrant Western reporters calling this a “Facebook” (or, insert your favorite social media site here) revolution? I’d like to state a fervent “no.” To do so is to take credit from the very brave individuals who’ve spent the past few days in the streets of Cairo and Suez, the individuals who’ve been shot at, some killed. To do so is to ignore the brutality, the tear gas, and the killings.

So, how are protestors in Egypt using social media?

I’d like to delve a bit into what I’ve seen on these various networks over the past, say 48 hours. Note that all of the following are merely examples, not the be-all end-all of what’s happening online in Egypt. And I fully expect my Egyptian friends to jump in with corrections, additions, and anything else they might like to add.

Let’s start with the extremely popular (423,000 members) “We are all Khaled Said” Page on Facebook, started last summer after the murder of young Khaled Said at the hands of policemen in Alexandria. Said’s murder resulted in a spate of loud, active blogging and tweeting, much of which was covered by Global Voices.

That solidarity page has morphed into what is perhaps one of the most central locations for information on the current protests in Egypt. Over the past 48 hours, many of the group’s thousands of members have posted photos, videos, and various other updates to the page.

Some of the links serve no organizational purpose and are intended simply to be shared broadly; others offer actual assistance: Take, for example, an update this afternoon, posted by a young woman whose profile says she’s based in Cairo, sharing the download link to the circumvention tool Hotspot Shield. An angry post from about 12 hours ago from the group’s admin ruminates on how the people of Suez were cut off from mobile networks when they needed them most. A Google Doc posted yesterday asks members of the Page to submit their email addresses in case Facebook is censored or the group is taken down (note: this very same group was taken down a month ago by Facebook because its admin was using a pseudonym, a TOS violation.)

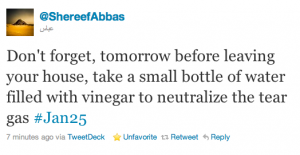

There are also events posted around Facebook. This one, for example, calls for solidarity between Muslims and Christians on Friday, asking them to unite in protest. A Google Doc (which I’ve been told is better not shared here) started prior to the January 25 protests, lays out a statement of purpose, explains meeting places, and offers practical advice: Egyptian flags only, no political emblems, no violence, don’t disrupt traffic, bring plenty of water, don’t bring your national ID card, etc.

Beyond Egypt, Beyond Right Now

To suggest that this type of organizing is limited to right now would be to ignore the existing use of digital tools in the region for social and political organizing. To be honest, so much of the rhetoric around the use of social media in Egypt and Tunisia makes me want to scream — folks act like these American tools just dropped from the sky like humanitarian food rations, set to save the people from their (American-supported, natch) dictators.

As Sami Ben Gharbia so eloquently noted on Al Jazeera’s Riz Khan program last week, these networks have existed for a long time. Are they enhanced by social media? Of course, and I’m sure Sami would agree. But when did we go from referring to social media as a tool to calling it the catalyst of a revolution?

I will leave this with a final thought cribbed from Ethan Zuckerman, who wrote last week: “Tunisians took to the streets due to decades of frustration, not in reaction to a WikiLeaks cable, a denial-of-service attack, or a Facebook update.”

Egyptians are not out in the streets because of Facebook, nor Twitter. They are not angry because an American diplomat who spent a few years in their country revealed something that a nation of Egyptians already knew. Egyptians are angry, and rightfully so, at a dictatorship that has been around for longer than I’ve been alive, a dictatorship that has been supported by the United States for almost as many years (see Alaa Abd El Fattah’s thoughts on that here). And if their will is to bring that dictator down, then so be it.

34 replies on “How are protestors in Egypt using social media?”

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Glyn Moody, Jillian C. York, Jillian C. York, Evgeny Morozov, Shaun Dakin and others. Shaun Dakin said: RT @jilliancyork: How are protestors in Egypt using social media? http://t.co/FZm0M2x […]

seems to befull block now

http://storify.com/wikinews030/jan28th-in-egypt-2011

calls for help on: http://storify.com/wikinews030/jan-27th-in-egypt

[…] Eine gute Zusammenfassung bietet auch Jillian C. York, die auf der kommenden re:publica zu Gast sein wird: How are protestors in Egypt using social media? […]

[…] Jillian York has a very interesting post on how Egypt's protesters have been using the Internet thus […]

[…] Jillian C. York » How are protestors in Egypt using social media? […]

[…] Jillian C. York » How are protestors in Egypt using social media? […]

Jillian C. York » How are protestors in Egypt using social media?…

Here at World Spinner we are debating the same thing……

I think to deny the use of new tools as exciting and noteworthy in a revolution is a mistake. You will likely remain frustrated as it is an inevitable story, and rightly so. There are new capabilities at play, such as Facebook’s secure sign on that change the game (nice post on that).

Framing the argument around using the tools to better activities that have predated technology makes a ton of sense. Carrier pidgeons and messengers were used before the telegraph and ham radio which preceded phone and email. All were used historically for revolutionary purposes, to galvanize human networks.

[…] How are protestors in Egypt using social media? This question has been posed to me constantly over the past two days from journalists doing their best to understand the relationship between online and offline forms of protest. I feel their pain – after the mainstream media went gaga over Iran’s 2009 protests, journalists must be considerably wary when tackling this subject: Go one way, and you risk overstating the influence, go the other and you’re dismissed as assuming individuals in the Arab world incapable of leveraging social media tools for organizing. […]

[…] How are protester in Egypt using social media? This entry was posted in Uncategorized. Bookmark the permalink. ← Chinese State Visit LikeBe the first to like this post. […]

[…] cable, a denial-of-service attack, or a Facebook update.” [ thanks also to Jillian York's post […]

[…] Twitter, no protests? Not quite: JK: I read your piece a couple of days ago on how the demonstrators are using social media. Has the black-out changed […]

It is really interesting to me that the analysis of the digital elements for Tunisia, Egypt, and Yemen is taking much longer than for Iran and Moldova. Partly it is because we are not jumping to facile and inaccurate labels. But are there other reasons? Is the analysis actually more difficult in the current situations or are analysts just being more cautious?

I would actually think it’d be easier this time around. In any case, I think it’s out of caution; we’ve seen how early analysis of Iran and Moldova were mostly wrong.

Although Egyptians are still offline, there are clearly savvy tacticians on the ground who know the the tactics of nonviolent civil resistance. This is the kind of knowledge that wins revolutions:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/jan/27/egypt-protest-leaflets-mass-action?CMP=twt_fd

[…] Jillian C. York » How are protestors in Egypt using social media? Jillian C. York (tags: egypt socialmedia protests activism comment speakers) […]

I was pleasantly surprised to hear you speak on Sci-Fri. Go science!

[…] não será isto que irá impedir as manifestações; como escreve Jillian C. York, a origem dos protestos não está nas redes-sociais e a interrupção das mesmas […]

[…] of Facebook campaigns that achieve real-world results, such as the 2008 General Strike and the “We are All Khaled Said” campaign. Yet a few days ago the government flipped the Internet “kill switch.” Not a single […]

[…] the Google executive who created the We Are All Khaled Said page on Facebook, widely credited as helping rally the original protests on January 25th. After his emotional televised interview on Dream TV, hundreds of thousands have joined a Facebook […]

[…] the Google executive who created the We Are All Khaled Said page on Facebook, widely credited as helping rally the original protests on January 25th. After his emotional televised interview on Dream TV, hundreds of thousands have joined a Facebook […]

[…] the Google executive who created the We Are All Khaled Said page on Facebook, widely credited as helping rally the original protests on January 25th. After his emotional televised interview on Dream TV, hundreds of thousands have joined a Facebook […]

[…] down one of the top Egyptian protest groups in December. The group’s administrators were using pseudonyms to avoid government retaliation , according to Harvard researcher Jillian York, a violation of Facebook’s rules. One of those […]

[…] Facebook groups does not mean that digital activism is valueless. If one Facebook group like We are All Khaled Said was critical in mobilizing a successful revolution in Egypt, then the phenomenon is worth looking […]

[…] wanted to know (and I quote) “exactly how Egyptians are using social media.” I wrote a blog post about it. I cheered a little inside that they were asking me (and more importantly, actual Egyptian […]

[…] There’s little debate that digital technology and social media facilitate activism: easy group formation and collaboration, near-free mass information dissemination, fast resource transfer, anonymity tools. Yet this facilitation is strategy-agnostic. It was just was easy to start “Saving the Children of Africa” as it was to start “We are All Khaled Said.” […]

[…] Jillian has been asked this question a lot in the last few days by journalists, “How are protesters in Egypt Using Social Media?” to help understand the relationship between online and offline protests. […]

[…] were revolting in Tunisia seemed to help trigger the same kind of response in Egypt, because it helped protesters in Tahrir Square in Egypt see themselves as part of a larger movement, or at least not alone in their desire to revolt. That’s a positive use of these tools […]

[…] were revolting in Tunisia seemed to help trigger the same kind of response in Egypt, because it helped protesters in Tahrir Square in Egypt see themselves as part of a larger movement, or at least not alone in their desire to revolt. That’s a positive use of these tools (unless […]

[…] were revolting in Tunisia seemed to help trigger the same kind of response in Egypt, because it helped protesters in Tahrir Square in Egypt see themselves as part of a larger movement, or at least not alone in their desire to revolt. That’s a positive use of these tools (unless […]

[…] were revolting in Tunisia seemed to help trigger the same kind of response in Egypt, because it helped protesters in Tahrir Square in Egypt see themselves as part of a larger movement, or at least not alone in their desire to revolt. That’s a positive use of these tools (unless […]

[…] were revolting in Tunisia seemed to help trigger the same kind of response in Egypt, because it helped protesters in Tahrir Square in Egypt see themselves as part of a larger movement, or at least not alone in their desire to revolt. That’s a positive use of these tools (unless […]

[…] were revolting in Tunisia seemed to help trigger the same kind of response in Egypt, because it helped protesters in Tahrir Square in Egypt see themselves as part of a larger movement, or at least not alone in their desire to revolt. That’s a positive use of these tools (unless […]

[…] networks are starting to play a huge role in social movements, such as the protests in Egypt (2011), and Hong Kong (2014) . Power will always exist through communications, so to focus on just […]