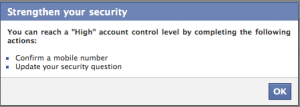

Logging into Facebook today, I was greeted with a little box in the upper right-hand corner of my screen, telling me that my security level was “low.” Intrigued (last week it was marked “medium), I decided to click.

Facebook has been trying to increase their security measures for awhile, a commendable effort. Unfortunately, once again, it appears they have their American users in mind, rather than their users (especially activists) around the world for whom Facebook’s terms and infrastructure can be problematic.

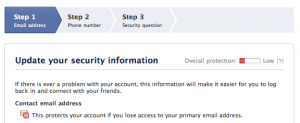

Facebook’s increased security measures come in three parts, outlined below. The first step isn’t particularly problematic – users are asked to provide alternative email accounts. This could, in fact, be one of the safest ways to regain access to one’s account if broken into: Simply provide a few anonymous, personally unidentifiable email accounts.

Step two is to provide a phone number – in some ways this is a good thing: if you lose access to one of your many email addresses you’ve provided, you can have a text message sent to your phone. On the other hand, if your phone is stolen (randomly, or let’s say for argument’s sake, by government security forces in Iran), you’d have quite the problem.

Step 3 is the most problematic. Let me ask you this: When asked to supply your mother’s maiden name as a “security question,” do you give a) your mother’s real maiden name or b) a fake, but memorable, response. If you answered b), you’re correct: There’s nothing “safe” about giving publicly identifiable information in order to retrieve your account; on the contrary, it only makes it easier for others to break in.

Fortunately, most companies recognize this and offer the opportunity to write your own security questions. Facebook, on the other hand, ignored best practices in their latest implementation and instead offered four choices, all of which contain relatively public information:

In case the image is too small, the four questions are:

- What was the last name of your first grade teacher? (I can think of at least 100 people that know the answer to this)

- In what city or town was your mother born? (public record)

- What are the last five characters of your driver’s license (if my wallet were stolen, this would be too easy)

- What street did you live on when you were eight years old? (my parents still live there, so that’s public too)

On the upside, the security updates page is offered in a number of languages this time around, including Arabic!

Now, I realize that most people have little reason to worry about their account being broken into. Rather, my concern is for the minority who do. You may think Facebook is safe, but if you’re an activist in another country and you’re using Facebook properly (e.g., following the rules and using your real name), you’re already at risk. Add to that the fact that a break-in would give access to your entire list of contacts, and potentially other identifying information (your phone number, your home address, perhaps even your credit card information) and you’re really unsafe.

Personally, I’ve chosen not to fill in the security questions. Instead, I’ve created a strong, long, unguessable password that I don’t use for any of my other accounts and have provided a backup e-mail address that no one knows. I feel safer that way.

8 replies on “Facebook’s New Increased Security Measures: Not Very Secure”

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Katrin Verclas and others. Katrin Verclas said: RT @jilliancyork: New blog post: Facebook’s New Increased Security Measures: Not Very Secure http://bit.ly/dRncMX (jilliancyork.com) […]

Your password on every website is different, right? Any site can be hacked.

I haven’t come across that Facebook security process yet… but I went through an equally annoying one yesterday due to sending multiple people friend requests with duplicate optional messages which caused the site to place me into spammer status — so I’m now blocked from adding new friends for 4 days.

Good article. There seems to be – in general – an overwhelmingly poor understanding of security principles among large websites. The whole secret question charade is certainly no better than an alternative password (if your answer doesn’t relate to or can’t be inferred from the question, e.g. a fake mother’s maiden name as you suggested), but most likely far *worse*, since most answers *can* potentially be found out with a little digging around. So all this mechanism does is provide an alternative, easier way to access the account if the password can’t be discovered.

Another thing that drives me mad is the arbitrary restrictions that some sites seem to place on passwords, e.g. limiting them to a certain number of characters and disallowing non-alphanumeric characters. There’s no technical reason that this should be necessary.

Also, Ari Herzog is right in that the really important thing is not to reuse passwords among lots of sites; at least not for ones that you actually care about. If one is compromised, then it’s straightforward for the attacker to use those credentials to gain access to other sites as well.

Your password on every website is different, right? Any site can be hacked.

For those I care about, yes. For Gawker, I had used a generic, unrevealing password. If it’s a site where I comment but leave no personal information, I’m less apt to care.

[…] Adding “increased security measures”…which include you providing yet more personal information. For them to sell. […]

A big thank you for your blog post.Much thanks again. Awesome.

Facebook asked for Last five characters of my driving Lisence. I never gave any characters to them as a security check so how would I know it ??

my Facebook account is locked & the security question u know

What was the last name of your first grade teacher?please tell what’s the correct answer of this question… help me