First, a note: I’m no expert on either of the two countries that are a focus of this piece, nor do I intend to be comprehensive in my analysis. I know a bit more about Syria than I do about Bahrain, having studied its history closely and traveled there, but nonetheless, I intend purely to focus on why these two countries are experiencing a phenomenon online that, thus far, no other country in the Arab world has experienced.

Social Media Wars

I’ve spent the past few months documenting the tactics of the Syrian Electronic Army and other factions in respect to spreading propaganda to counter anti-opposition sentiment (you can find my writing on the SEA here, here, and here; and an interview with NPR here). I’ve mainly focused on the utility of hacktivism in awareness-raising, with some emphasis on the effectiveness of flooding the dominant media narrative for the purpose of gaining attention for the other side (in this case, the pro-regime side), but what I haven’t touched on is the longer-term effect these tactics are having on people both in-country and outside, as well as where this type of activity fits in the broader landscape of online activism in the region.

I’ll say a few things up front. First off, that these heavy propaganda tactics on social networks are unique to three countries in the region: Syria, Bahrain, and in a different sense, Israel. Let’s ignore the third one for a moment; primarily because its impact is less dangerous, but I’ll nonetheless touch upon it later, because I think its tactics are relevant.

Syria and Bahrain are in many ways two very different cases. While the regime in Syria has at this point been widely condemned and sanctioned (after months and months), Bahrain still enjoys support from the United States and other Western countries, with no end in sight. The state of the Internet in the two countries is also extremely different: While Bahrain enjoys Internet penetration in the high 80% range, Syria’s access remains below 20%. Syria’s uprising has gone on now for nearly eight months, while Bahrain’s has ebbed and flowed. Both countries have nonetheless employed harsh tactics against Internet users, filtering opposition websites and arresting dissenting bloggers.

There is one major similarity between the two countries that often goes unmentioned in mainstream coverage: in both countries, opinion on the ground–and online–is divided. Some bloggers seem hesitant to dwell too much on this; and I, while cognizant of it, am not entirely educated of the reasons. I therefore won’t go deeply into the reasons, though it’s obvious that some are purely sectarian, while others are a result of individuals benefiting from the regimes. It is also, therefore, worth noting that Bahrain and Syria are both controlled by minorities: Bahrain by its Sunni minority (estimated at less than 20% compared to the Shi’a majority estimated at 70%), and Syria by its Alawi minority (Sunnis make up nearly 74% of Syria, Alawis are estimated to comprise 10%).

Countries Divided

The fact of divided opinion differentiates Syria and Bahrain greatly from Egypt and Tunisia on several levels. Online, anyone closely following the blogospheres of those four countries would be well aware of that fact. Whereas the Egyptian blogosphere has been divided for years upon various political lines (e.g., leftists, secularists, Muslim Brotherhood, etc), it has always had one thing in common: disgust for the Mubarak regime. The Tunisian blogosphere, though I don’t know it as well, was similar in its attitude toward Ben Ali.

The Bahraini and Syrian blogospheres, both of which I’ve followed for quite some time, are diverse. In Syria, there has always been a pocket of dissenters, from those willing to speak out harshly against the regime to those who raise more specific points, such as its heavy control over the Internet. There have also always been a range of other views, from those favoring reform to those who outright support the regime to those who choose not to speak of it.

Of course, as I mentioned, both countries are also divided on the ground. Syria’s pro-regime rallies have become infamous (warning: links to SANA), while Bahrainis in favor of the monarchy also responded with rallies of their own.

Keeping in mind the background, it becomes a bit easier to analyze the (online) events of this year.

The Propaganda Wars

In February, New York Times journalist Nick Kristof visited Bahrain and tweeted about his observations, re-telling the stories of victims and later wrote a column about his experience in the country. Almost immediately, he was hit with accusations of bias on Twitter, as well as petition directed at his Times editor urging him to be let go. Later, the tweets turned uglier, as Kristof was hit with death threats.

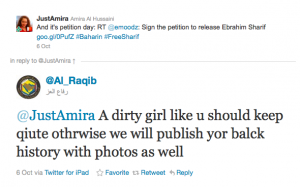

Over the course of the next few months, the Bahraini Twitter trolling continued, and was soon followed by a similar phenomenon in Syria. While Bahraini Twitter trolling was organized from the very beginning, with apparent individuals targeting specific commentary, in Syria it was a different story; most trolls appeared to be automated feeds targeting the #Syria hashtag in an attempt to flood it, not with misinformation, but with irrelevant information. Though some individuals, such as myself, were targeted directly (and with my own Flickr photos of Syria, no less), Twitter’s infrastructure makes it relatively easy to block and report accounts for spam, and while many remained up, most were removed from search, making it easier for those using the #Syria hashtag to follow events on the platform.

While Syrian online propaganda is likely state-sponsored (in some way or another) and has utilized a variety of platforms, from the hackings of Harvard University and other websites, to the retaliatory defacement of Anonplus, to spamming Facebook accounts of celebrities and politicians, and smear sites like the Plot Against Syria, Bahrain’s has remained largely on Twitter, and appears to be largely the work of individuals.

For some, the Bahraini trolling appears to be effective, at the very least in silencing opposition voices abroad. For each tweet using the Bahrain hashtag, as I noted last week at #AB11, the Twitter user will receive a flood of tweets, and many seem to have decided it simply isn’t worth the hassle. The propaganda therefore succeeds. Of course, Bahrain is also employing a slew of other propaganda tactics, such as placing opinion pieces in American newspapers with the help of American communications firms. Not that they need it, of course. The State Department is all too willing to uphold the Bahraini regime.

In Syria, I’d say it’s a different story. The majority of the efforts are so sloppy and ineffectual that they’re unlikely to convince anyone of their

In the end, however, propaganda is just a distraction. It is effective, perhaps, in silencing voices, but the real threats are on the ground and in the tensions in those two countries between opposition and regime supporters. Nevertheless, it makes sense to continue studying it–perhaps by more quantitative means–to understand its effects both on the ground and in terms of external support.

Addendum: Israel

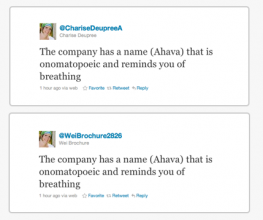

I mentioned Israel in a note at the beginning of my piece. While I don’t think that it fits into the context of this piece, I have seen considerable efforts, both by Israeli companies like Ahava and–apparently–government-supported groups, to utilize some of the same techniques as Syria and Bahrain, particularly on Twitter. Just a few days ago, one account (called @freemiddleeast and associated with this website) tweeted to me after I used the word “Palestine,” indicating that it was using automated software to target certain search terms. The account was quickly blocked for spamming, to Twitter’s credit, but others remain.

Israel, like–perhaps–Syria, also pays individuals to generate propaganda, which is apparent from some of the accounts that have targeted me (they’re rife with misspellings and often, total misinformation).

Of course, Israel is not alone in its attempts. The US State Department has its own team that targets “inaccurate speech” in Urdu, Arabic, and Farsi (to their credit, however, their paid propagandists are required to identify as such), and earlier this year it was revealed that CENTCOM would undertake similar, less transparent efforts. Thus far, I’m not aware of any other democratic states engaging in such practices, however.

Conclusion

It’s hard to say what long-term effects online propaganda from the aforementioned countries might have. At an event last month, Alec Ross (Senior Advisor for Innovation to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton) proclaimed that the days of (traditional) propaganda were over. I disagreed with him, noting the online attempts at propaganda, and while he assented, I suspected that the administration views these types of propaganda as different from those of, say, state television. I do not. I think the pervasiveness and the distributed nature of social media propaganda makes it potentially more dangerous for its targets, as it creates a gang mentality and allows for the smearing of far more individuals than state media would ever make time for.

Of course, I’m obviously only tipping the iceberg with this post. I’m attempting to raise awareness of this phenomenon in the hopes that someone will take it on as a study, and would be happy to discuss further with anyone with interest.

29 replies on “Twitter Trolling as Propaganda Tactic: Bahrain and Syria”

[…] manages to pull it all together like Apple has done – there won’t be an iPhone killer.Now, before we go any further I completely subscribe to the concept of to each their own. I personal…ung, Nokia or cheap Chinese knockoff. I am an Apple fan as evidenced by the Macbook I’m typing […]

[…] a 34952 estate planning lawyer will go a long way toward protecting your assets and loved ones. Before you meet with a 34952 estate planning lawyer, get smart, get organized. Being prepared can he…your family legacy and bring greater piece of mind […]

[…] Jillian C. York schreibt darüber, wie in Syrien und im Bahrain Sicherheitsbehörden wahrscheinlich auf Twitter rumtrollen: Twitter Trolling as Propaganda Tactic: Bahrain and Syria. […]

I agree with you. I feel that allot of misinformation is going around about Libia also. It has all happened about the same time. Also Un and NATO have been ridiculed to try and discredit their work or try to eliminate them alltogether. They want to keep dictators that they have been dealing with and screw Democracy. Wiining dictators and not the people has never brought will it ever bring peace.

[…] Twitter Trolling as Propaganda Tactic: Bahrain and Syria […]

[…] Jillian C. York: Twitter Trolling as Propaganda Tactic: Bahrain and Syria: here. […]

[…] Jillian C. York: Twitter Trolling as Propaganda Tactic: Bahrain and Syria: here. […]

[…] especialy since the beginning of the Arab Spring, in January 2011. Twitter has proven to be a solid propaganda platform used by many authoritarian […]

[…] especialy since the beginning of the Arab Spring, in January 2011. Twitter has proven to be a solid propaganda platform used by many authoritarian […]

[…] especialy since the beginning of the Arab Spring, in January 2011. Twitter has proven to be a solid propaganda platform used by many authoritarian […]

[…] [2] https://jilliancyork.com/2011/10/12/twitter-trolling-as-propaganda-tactic-bahrain-and-syria/ […]

[…] To find examples of this, one need only look to the governments—such as China, Israel and Bahrain—that employ paid commenters to sway online opinion in their favor. And of course, there are […]

[…] To find examples of this, one need only look to the governments—such as China, Israel and Bahrain—that employ paid commenters to sway online opinion in their favor. And of course, there are […]

[…] To find examples of this, one need only look to the governments—such as China, Israel and Bahrain—that employ paid commenters to sway online opinion in their favor. And of course, there are […]

[…] principal. Para encontrar ejemplos de esto, solo hay que mirar a los gobiernos como China, Israel y Bahrein, que emplean comentaristas pagados para influir en la opinión en línea a su favor. Y por […]

[…] principal. Para encontrar ejemplos de esto, solo hay que mirar a los gobiernos como China, Israel y Bahrein, que emplean comentaristas pagados para influir en la opinión en línea a su favor. Y por […]

[…] principal. Para encontrar ejemplos de esto, solo hay que mirar a los gobiernos como China, Israel y Bahrein, que emplean comentaristas pagados para influir en la opinión en línea a su favor. Y por […]

[…] principal. Para encontrar ejemplos de esto, solo hay que mirar a los gobiernos como China, Israel y Bahrein, que emplean comentaristas pagados para influir en la opinión en línea a su favor. Y […]

[…] Para encontrar exemplos disso, é preciso apenas olhar para governos – como a China, Israel e Bahrain – que empregam e pagam pessoas para comentarem e influenciarem a opinião online a seu favor. E […]

[…] Para encontrar exemplos disso, é preciso apenas olhar para governos – como a China, Israel e Bahrain – que empregam e pagam pessoas para comentarem e influenciarem a opinião online a seu favor. E […]

[…] hierfür zu finden, muss man sich nur Regierungen anschauen – solche wie China, Israel und Bahrain – die bezahlte Kommentatoren engagieren um die Meinung der Regierung online zu verbreiten. Und […]

[…] hierfür zu finden, muss man sich nur Regierungen anschauen – solche wie China, Israel und Bahrain – die bezahlte Kommentatoren engagieren um die Meinung der Regierung online zu verbreiten. Und […]

[…] hierfür zu finden, muss man sich nur Regierungen anschauen – solche wie China, Israel und Bahrain – die bezahlte Kommentatoren engagieren um die Meinung der Regierung online zu verbreiten. Und […]

[…] Para encontrar exemplos disso, é preciso apenas olhar para governos – como a China, Israel e Bahrain – que empregam e pagam pessoas para comentarem e influenciarem a opinião online a seu favor. E […]

[…] exemplos disso, é preciso apenas olhar para governos – como a China, Israel e Bahrain – que empregam e pagam pessoas para comentarem e influenciarem a opinião online a seu […]

[…] zu finden, muss man sich nur Regierungen anschauen – solche wie China, Israel und Bahrain – die bezahlte Kommentatoren engagieren um die Meinung der Regierung online zu verbreiten. […]

[…] des exemples de cela, il suffit de regarder pour les gouvernements, tels que la Chine, Israël et Bahreïn qui emploient des commentateurs payés pour influencer l’opinion en ligne en leur faveur. Et […]

[…] des exemples de cela, il suffit de regarder pour les gouvernements, tels que la Chine, Israël et Bahreïn qui emploient des commentateurs payés pour influencer l’opinion en ligne en leur faveur. Et […]

[…] exemples de cela, il suffit de regarder pour les gouvernements, tels que la Chine, Israël et Bahreïn qui emploient des commentateurs payés pour influencer l’opinion en ligne en leur […]