Article by Stéphanie Vidal under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence

First published by Slate.fr

Known worldwide as a free Internet defender and an Open Source culture promoter, he has been detained for three years and a half by the Bashar al-Assad regime and has been transferred from Adra prison to an unknown place on 3 October 2015. On 10 October, his wife was informed that his name has been deleted from the prison register, without further information on where he could be. None of the parties involved recognises they have him or not.

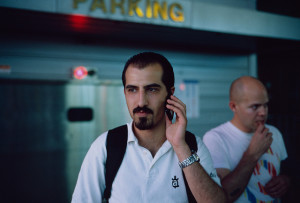

Bassel Khartabil, 34, fervent defender of a free Internet and promoter of open source culture, has been held prisoner since 15 March 2012 in the jails of the Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad. According to the opinion of the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention during its 72nd session, held in Geneva in April 2015, he would be arbitrarily detained for “peacefully exercising his right to freedom of expression” and having “advocated a non-restricted use of the Internet.” He was transferred on October 3, 2015 from the Adra prison, located in the north-eastern outskirts of Damascus, where he was imprisoned since December 2012, he was taken to an unknown location, possibly for trial. Accused without evidence having ever been presented against him, he is more than ever in danger.

Developer recognized worldwide for his contributions to open source projects such as Mozilla Firefox, Wikipedia and Creative Commons, Bassel Khartabil was also involved in local action, based in Damascus on Aiki Lab, a place dedicated to digital art practices and teaching of collaborative technologies. For all of his work, he was awarded by the Foreign Policy website 19th position of its prestigious Global Thinkers ranking of 2012 and in 2013 won the Digital Freedom Award from the Index on Censorship, an international organization that has promoted and defended freedom of expression since 1972.

His imprisonment and his recent transfer deeply affect and concern the Open Source community and the militants and activists for human rights and fundamental freedom as is the free communication of thoughts and opinions. At the announcement of the news, Jillian C. York, director of the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), an organization defending civil liberties in the digital world, posted on her Twitter account the following message:

We know petitions won’t convince Syria (or anyone) but it’s all we’ve got. Please help get the word out so Bassel stays safe.

— Chillian J. Yikes! (@jilliancyork) October 3, 2015

In less than 140 characters, Jillian C. York managed to raise two realities: the frightening silence of the Syrian government in response to the actions taken for the release of Bassel Khartabil and the protection power that lies in the watchfulness of the Internet users for political prisoners fate. On the first point, Ines Osman, Coordinator of the Legal Service of the Alkarama Foundation, NGO linking the victims of violations of human rights in the Arab world and the UN mechanisms, confirms the impassivity of the Syrian authorities:

We have taken action at the UN twice, in 2012 and 2014, and the Syrian authorities have never responded to UN requests. This past April, the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention called for the release of Bassel,and this appeal once again remained ignored. It is essential that the international community is calling for the implementation of these decisions, which clearly states that his most basic rights were not respected: he was arrested, held incommunicado, tortured and brought before a military judge with false accusations.

On Saturday morning, we were informed that Bassel has been transferred from the Adra jail towards an unknown destination, nobody knows his present whereabouts. We immediately informed the Working Group on forced missing persons. We hope that this time, the Syrian authorities will answer.

When there is no longer respect for human rights, public calls can only state what one hopes for. This brings us to the second point: the more the affirmation of our hope will be shared and present on the Web and social media, the more it may turn to a reality. Bassel’s engagement in favour of a free Internet may have brought him to jail, but the attention that we, citizens on the Internet, give to this case may, to some degree, help bring him out of the darkness. To demonstrate interest for his life is one of the ways by which people can become aware that in Syria, one can die because one uses a smartphone and understands how the Internet works.

Survival in Adra, even under the bombings

To tell Bassel’s story over these last five years, is also to try to portrait implicitly a devastated Syria, from the beginning of the Syrian revolution from betwen the 15-18 March 2011 (first calls to uprising, further to the Egyptian revolution; first “Friday demonstrations” and their brutal repression) to the slow transformation of this revolution into an inextricable armed conflict where 240,000 people died and millions were displaced.

Bassel Khartabil, who was forced by restraint to remain in Syria, is yet another of these prisoners whose number is hard to establish: one speaks of 8,000 prisoners, of which 600 women, for the sole Adra jail, three times its nominal capacity. Prisoners have been jailed in Adra for a wide variety of motives such as drug dealing or use, murder or robbery, but it also detains prisoners whose name is known abroad for the engagement in favour of freedom of expression. Mazen Darwish, for instance, is one of them. He is the President of the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression, arrested in February 2012, almost a month to the day before Bassel Khartabil. He was freed temporarily on 10 August 2015 before being found not guilty of the charges of “publishing information on terrorist acts” on the 31st of the same month.

Detained under other charges, Bassel Khartabi was accused in front of military courts, and thus excluded from the general political amnesty of June 2014, which, though opaque, cleared many pacific militants from the charges brought against them. He was thus still in Adra when the jail was taken by assault by the armed rebel group Jaysh al-Islam, who took control of two of its buildings on last September 12th, a date that may be symbolic since being the day after Bashar el-Assad’s fiftieth birthday. The prisoners found themselves caught between the bombings by the regular army and fire by the rebels trying to free the jail. Bassel Khartabil survived to this deluge of fire, but it seems that around twenty other prisoners were killed and several several dozens, possibly a hundred, were injured.

Again, when it comes to Syria, information sources are difficult to obtain. Numbers are approximate, speech choke in fear and communication is slowed because of regime surveillance. As stressed by the lawyer Benoît Huet in an op-ed published in the French newspaper Libération, the war in Syria has also become, in a connected world, an information war, raising the question of its dissemination and manipulation. At international level they are known, this information war prevents us clearly see the facts in a media-pervasive but terribly distant conflict because of its extreme complexity. It should not make us overlook the other information war, which raged this time at local level: in the heart of Syria, personal information and content posted on social networks are used as weapons.

Syrian smartphones, fear in the pocket

Internet, and particularly social media such as Facebook, have been privileged communication means by Syrian population to testify of the revolution of 2011 and the regime bloody repression. The documentary Syria: Inside the Secret Revolution initially broadcast by the BBC on 26 September 2011, gathers some of these videos which, after their publication online, allowed the international community to realize the revolt on Syrian streets.

the people who are in real danger never leave their countries. they are in danger for a reason and for that they don’t leave #Syria

— Bassel Safadi (@basselsafadi) January 31, 2012, two weeks before his arrest

It should nevertheless not be forgotten that Internet has not always been authorised in Syria, nor Facebook accessible to its population. As he took office after the death of his father Hafez in June 2000, Bashar el-Assad appeared like a reformer demonstrating opening spirit in several economic and political domains. He even made access to Internet possible but, understanding the power of the network, took care of having most social networks censored in 2007, followed by Wikipedia in Arabic in 2008.

From the start, the network was monitored: those who would go to cybercafés had to show proof of identification and their web history was kept, as explains Wahid Saqr, former officer of security of the Syrian government to the mic of Mishal Husain in the second episode of How Facebook Changed the World: The Arab Spring another documentary broadcast by the BBC on 15 September 2011.

It is only in February 2011 that Bashar el-Assad made possible connections to Facebook, YouTube and Twitter. The gesture, intended to be magnanimous, was quickly interpreted as threatening, social networks appearing as a useful tool for the govenrment to surveil its population and gather information on those who could, through words and images, be opponents. Employed as digital surveillance weapons, they have been used to track those whose voice could rise, virtually or for real, against Damas regime, but also all those who had computer means or competences.

Dana Trometer, researcher and producer of the documentaries quoted above, could feel this deadful reality:

People whom I met for all movies on which I worked on the Arab world, and especially of Syria, have very often been forced to escape or have unfortunately disappeared little time after our interviews.<

Even today, on the road of exile, refugees explain that it is particularly dangerous to carry a mobile phone. This simple possession can lead to arrestation—or much worse—by Syrian government representatives or ISIS members who ask them, at their respective checkpoints, to give their Facebook username and password to determine their political allegiance.

Bassel Khartabil was saying that in Syria, holding a mobile phone was much more dangerous that walking around with a nuclear bomb. Because of his job of developer and his commitments to the promotion of a free Internet, it was impossible for him to get rid of his comuters and connected mobile phones, nor to have his Information Technologies competences forgotten. On 31 January 2012, two weeks before being arrested, he posted the following tweet: “the people who are in real danger never leave their countries. they are in danger for a reason and for that they don’t leave Syria.

>Wanting to build: the AikiLab and Palmyre Project

His role of Creative Commons lead in Syria and his participation, at the international level, in the free culture movement, led him to frequent travels abroad, but he would always go back home. It was in Poland, at the September 2011 Creative Commons Summit, that his friend Jon Phillips, who became since then the leader of the #FreeBassel campaign, saw him for the last time:

I begged him to not go back, that he would be killed or made prisoner. He tried to reassure me by telling that maybe he would not be risking that, and that anyway, his friend, his family, his love was there, that he could not stay. We cried and it was really ugly, then we spend the rest of the night laughing and designing a new world. When the sun rose, he took his cab, waved a last time through the open window, and I remember telling me that it was the last time I was seeing him, that he would get arrested as soon as out of the plane.

It didn’t exactly happen like that: Bassel Khartabil got a few more months of respite, during which he continued his local engagement. Syria being under embargo, only certain proprietary softwares had received the authorisation to be taught in universities. Bassel Khartabil had thus founded in 2010 the AikiLab, described—depending on the person doing the describing—as a hackerspace or a cultural center, in order to allow education to social media and open source technologies.

Developers, artists, professors, journalists and local entrepreneurs would frequently visit: the Aiki Lab, as described by artist Dino Ahmad Ali, was a large apartment with two rooms where anyone could come work and even sleep if the task was long, take a coffee or a beer in the kitchen to give oneself courage or relax. The large living room was fit for conferences and Internet celebrities visited to share their knowledge, such as Mozilla founder Mitchell Baker and MIT Media Lab director Joi Ito.

Dino Ahmad Ali and Bassel Khartabil were also colleagues. They were both working for a publishing house called Al-Aous, on Discover-Syria.com, a website proposing cultural information on Syria—Dino as artistic director and Bassel as technical director. Always for the same company, Bassel Khartabil dedicated himself for years to a project which was particularly close to his heart, the Palmyra Project. On CD-Rom, this project imagined a virtual visit of the antique city, fully reconstructed in 3D images from documents of scientific and archeological research. “Initially, Bassel was only dealing with programming, but as a person with multiple talents, he learned to use the Maya software and realised 3D modeling,” remembers Georges Dahdouh, who joined the team several months as head of 3D modeling. “He also learned the functioning of a game engine to conceive the path of the virtual visit in 3D and at the end, together with other team members, he would work on evey other aspect, except copyright and research, as a team was dedicated to the study of historical sources and interviews with archeologists.”

Oriented for a general audience, Project Palmyra was expected to constitute a sort of digital encyclopedia on this city also called Tadmor, its restitution gathering images and texts and its realisation gathering IT specialists and archeologists. Khaled Al-Assad, director of antiques of Palmyra between 1963 and 2003 and friend of Bassel Khartabil, was one of those. This scholar was beheaded on 18 August 2015 by ISIS, before his body was exposed on the streets by his executioners and photos broadcasted on social media.

If the CD-ROM has not been edited as of today, the members of the #FreeBassel campaign decided to revive Palmyra Project by launching on 15 October 2015 #NewPalmyra, an online community and a platform of data storage, in order to honour the work of Bassel. A project directed by Barry Threw, digital artist and director of software for Obscura, who also contributed to allow technically #racingextinction, a video projection on the Empire State Building. Behind both hashtags, a similar desire, use architecture to raise public awareness, by displaying endangered species on one of the most famous skyscapers in NYC, by raising awareness on climate change, or by putting digital technology at the service of a threatened Syria:

The Ancient City of Palmyre was a vital gateway for commerce and cultures. With #NewPalmyra, we oppose the foolish destruction of archeological treasures led by ISIS à la destruction insensée des trésors archéologiques à laquelle se livre ISIS by the will of construction of a man like Bassel Khartabil. We hope this project will raise awareness on his work and contribute to his liberation.

A civilian pursued by a military tribunal

It is at the exit of his job, located in the district of al-Mazzeh in Damascus, that Bassel Khartabil was arrested on 15 March 2012 by the men of Branch 215, one of the military intelligence services in Damas. After having been interrogated and tortured for five days, he was accompanied to his house so that his computers and documents could be seized. He was then detained in secret for nine months. We know since then that he was first led to the Branch 248 of military intelligence and that he spent eight months in solitary confinement in the Adra prison. He was there presented to a military count on 9 December 2012.

The military court, specialised in trials of military criminals in times of war, obeys to the Defense minister and not to the Justice minister. It is composed of three miliraries, including one president. Its procedures are kept secret, accused do not have the right to a lawyer’s assistance, explains Noura Ghazi, attorney and human rights activist, who had gotten engaged to Bassel Khartabil a short time before he got arrested. Sentences are particularly severe and can go to death. Penalties are executed immediately, preventing any re-examination of the sentences. Since 2011 events, the military court was activated to persecute pacifists such as Bassel, Anas and Salah Shughri and many others. It is a clear violation of the law, the Constitution and even the founding decree of this court.

A civilian without a lawyer trialed by a military court, Bassel Khartabil saw his trial last no more than a few minutes, without any evidence advanced against him, as underlined the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention. After this expedite and unfair trial, he was immediately transferred to the prison of Sidnaya, known to be one of the most infamous of the regime

He was then sent to the prison of Adra, he could receive a visit of his family on 26 December 2012. They found him in an alarming physical and psychological state. He obtained the right to marry Noura Ghazi in the prison on 7 January 2013. He has been detained in Adra until 3 October 2015. According to a message posted on that day on the Facebook page of the #FreeBassel campaign, he was “transferred to the Adra prison to an unknown location after a patrol, which origin is unknown, came to ask him to get ready. It is assumed that he has been transferred to the headquarters of the military police civil tribunal in the district of al-Qaboun. Once more, we do not know where Bassel is, and are very worried.”

Bassel Khartabil, developer, teacher and pacifist, who survived torture, solitary confinement, hunger and bombing, certainly survives under the blade of a terrible sentence. Do not forget

Article by Stéphanie Vidal.

First publication in French on 9 October 2015 in Slate.FR

Translation into English by Philippe Aigrain, Mélanie Dulong de Rosnay, Jean-Christophe Peyssard.

Due to international emotion raised by Bassel Khartabil’s fate, Slate decided to share this article under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. Republication is free, please mention the author Stéphanie Vidal and the media of first publication, Slate.fr.