For awhile now, I’ve been thinking about the line between rights and responsibilities. I find it imperative to fight for the broadest possible rights and freedoms, but as an individual, I also find it imperative to act responsibly in my speech. That is why, despite being an atheist, you won’t see me insulting religion or the religious, even though I firmly believe it is my right to do so.

A few weeks ago, an advertising campaign by the odious Pamela Geller turned up in San Francisco. The advertisements, run on the MUNI buses, read: “In any war between the civilized man and the savage, support the civilized man. Support Israel. Defeat Jihad.” As a free expression advocate, I was shocked to hear people I count amongst my friends suggesting that MUNI should not have run the ads. As disgusting as they are, MUNI as a public agency is (as far as I understand, but I’m no legal expert) obliged to uphold the First Amendment, though its own terms of service for advertisements are indeed more restrictive (for example, I’m sure they would not allow nudity). My stance at the time was that the ads would be better dealt with by a responsive set of ads; furthermore, my feeling was that, by allowing those ads, MUNI would not be able to turn down any pro-Palestine ads in the future (something which local activists on the other side have fought against in the past).

So I tweeted my stance: That I support Pamela Geller’s right to free speech but that I find her views absolutely disgusting and that they should be denounced. Immediately, I was met with reaction from some of my fellow Americans, who claimed that I was “against free speech” for denouncing Geller’s views. This is utterly ridiculous, yet exemplifies the misguided views on free speech held by many Americans: They believe that freedom is without responsibility, that because you can say something, you should, and that odious views–rather than the legal right to express them–should be defended.

Incidentally, I feel that MUNI handled it perfectly, putting up a set of their own counter-ads denouncing Geller’s statements and donating the profits from hers to charity. I also feel that Obama’s denouncement of the recent video (more on that in a moment) was apropos: We should defend the legal right, yes, but we should also denounce views that are hate-filled.

This same issue arose a week or so later when, after his hate-filled tweets and shady dealings with the Malaysian government were exposed, columnist Joshua Treviño was dismissed from the Guardian. I was pleased by the paper’s decision and tweeted such, and once again was met with a chorus of “you don’t really believe in free speech!” Indeed, I do, and would defend Treviño against government censorship or, for that matter, censorship by private entity (such as Twitter) but I do not believe that everyone has the right to be paid and published in the mainstream for their views.

Cut to this week: A video, originally attributed to one Sam Bacile, is shown on Egyptian television, sparking riots outside the US Embassy, later spreading to other countries. The video is incredibly ridiculous, but also offensive to many Muslims, as it depicts the Prophet as a philanderer and all sorts of other nasty things. The video, as it turns out, was also made without the consent of the actors in it (that is, their lines were partly dubbed over) and happened to be made by an Egyptian Copt, seemingly with the goal to fan the flames of conflict.

Although its showing on television may have been what sparked the riots, the film is also partly available on YouTube and so, after the news of the riots spread, people (presumably including many people in the Middle East and in other Muslim countries) began checking it out. Within a day, Afghanistan had blocked YouTube (despite the country’s Internet penetration being well below 5%). Shortly thereafter, YouTube–after determining that the video was not against their ToS–geo-blocked access to the video in Egypt and Libya, where riots the day before had resulted in the death of the US Ambassador and three of his colleagues.*

My full reaction to Google’s actions are written here, in a piece for CNN, but for those who don’t feel like clicking, are summed up in the final paragraph of that piece:

…by placing itself in the role of arbiter, Google is now vulnerable to demands from a variety of parties and will have to explain why it sees censorship as the right solution in some cases but not in others.

Another great piece on the subject (in which I happen to be quoted) is this one by Ari Melber for the Nation.

What I did not write in my article, and what I have not said to the press, is this: In a globalized world, we cannot treat any one group with kid gloves. And yes, I mean Muslims.

See, here’s the thing: I understand why Muslims get angry when the Prophet is insulted. I understand the importance of the Prophet to Muslims, and I therefore do not participate in insulting Him. For what it’s worth, I also don’t insult Jesus or other religious figures, though I am a bit more casual in my language (that is to say, I’ve been known to casually throw around “Jesus Christ!” as an exclamatory, a holdover from my childhood).

At the same time, yes, I think it’s fucking ridiculous that violence has so often been the result of provocations to Muslims. Of course I also understand that rioting isn’t solely about this video, that there’s history behind it, much of which has to do with genuine Western support of Muslim oppression, but nonetheless: This violence is ridiculous and plays directly into the hands of those who provoke.

So when Google chose to block the video in Egypt and Libya, my reaction was one of frustration, for two reasons: First, it reeks of paternalism – who is Google to decide what’s best for the Egyptian or Libyan people? Second, why treat Muslims with kid gloves?

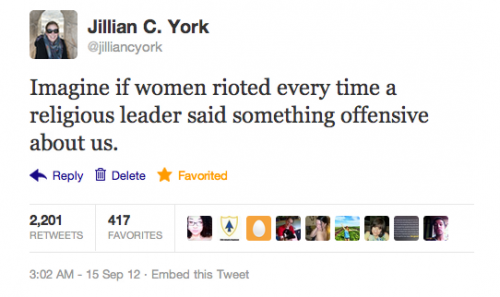

In the latter line of thinking, I tweeted the following, which has gotten a shocking number of retweets:

The thing is, religious leaders (Muslim, Christian, and others) say disgusting things about women on a regular basis. I’m reminded in particular of an Egyptian ad from a few years back comparing women to lollipops and suggesting that such “lollipops” must remain covered lest they end up covered in flies. Would Google allow that to remain up? Of course. And yet, as a woman, I find it directly offensive to my entire (living) gender, more so than a video insulting a Prophet who is no longer alive.

And there’s the rub: You don’t see women rioting every time we’re gravely insulted (there’s a Yoko song on in my head right now), which happens on a daily basis. And so, it is assumed, there is no reason to censor. But because there has been a trend over the past decade of Muslims reacting with violence,** our reaction is to stop the tide with censorship.

Google’s statement cited the “very difficult situation in Libya and Egypt” as their reason for blocking the video in those countries. I could respond with a million reasons as to why censorship isn’t the answer (Streisand Effect, the idea that bad behavior will be rewarded, etc), but ultimately what it comes down to is this:

We’re intertwined, us folks from all over the world. What happens in Cairo now matters to San Francisco, and vice versa. We are global, and if we are to live together, we must live by a set of universal values. And while those values must not be dictated by the West, ultimate freedom is, in the end, the only approach to speech that works. We cannot pick and choose who deserves speech, nor can we pick and choose who should be protected from insult.

*The latest news suggests that the attacks on the Libyan Consulate in Benghazi were pre-planned and that the riots may have just been a cover for carrying them out.

**To be clear, I am not of the school of thought that believes Muslims to be more violent than other groups, or inherently violent, or anything–but one would have to be blind not to observe a trend of violent reaction to insulting the Prophet.

7 replies on “On Rights and Responsibilities, “Hate Speech,” and Google Paternalism”

In temporarily blocking the video in some countries, legal experts say, Google implicitly invoked the concept of “clear and present danger.” That’s a key exception to the broad First Amendment protections in the United States, where free speech is more jealously guarded than almost anywhere in the world.

“Imagine if women rioted everytime a religious leader…”

Deepity!

Being a woman does not involve brainwashing within a cult. Women don’t believe themselves to be superior to others. And most importantly, being a woman does not entail sacralizing someone/something.

Show me one legal expert that has said that.

[…] On Rights and Responsibilities, “Hate Speech,” and Google Paternalism, Jillian York blog post […]

It was a pleasure reading this. Thank you for presenting your idea with such calm and clarity.

I am a Muslim. I am from Pakistan. (feels like giving out a disclaimer) :)

It would be an understatement to say that I disagree with the violent reaction Muslims show. I feel disgusted that there is violence.

Also, thank you for actually using “freedom of speech” and the word “responsibility” in the same sentence. Don’t see that often. That was comforting.

The question is, there is a difference between argument and insult. We can talk about it, or we can have a go at it. People understand the difference between this. Why can’t there be a clear stance in not being abusive? Words hurt. Do they not? Why can’t there be a reasonable debate on that? You can offend me in presenting an argument, but you should not be allowed to offend me for the sake of playful banter. Imagine teachers allowing kids to do that at the playground in the name of freedom of speech.

I wonder how (or rather, why) would I allow someone to deliberately use hateful words against you. Google, for example, clearly says that it won’t allow hateful speech. Is there a difference in the definition of “hateful” ? Hardly a few years ago, it was common to find the “N” word being used freely. Now it is considered hateful. It took the African American population a lot of struggle to arrive at this stage. It shouldn’t have been like that. Someone pleading the “freedom of speech” right to openly be racist is not tolerated. Why is that? What makes intolerance towards racism different from intolerance towards religion?

It was a pleasure reading this. Thank you for presenting your idea with such calm and clarity.

I am a Muslim. I am from Pakistan. (feels like giving out a disclaimer) :)

It would be an understatement to say that I disagree with the violent reaction Muslims show. I feel disgusted that there is violence.

Also, thank you for actually using “freedom of speech” and the word “responsibility” in the same sentence. Don’t see that often. That was comforting.

The question is, there is a difference between argument and insult. We can talk about it, or we can have a go at it. People understand the difference between this. Why can’t there be a clear stance in not being abusive? Words hurt. Do they not? Why can’t there be a reasonable debate on that? You can offend me in presenting an argument, but you should not be allowed to offend me for the sake of playful banter. Imagine teachers allowing kids to do that at the playground in the name of freedom of speech.

I wonder how (or rather, why) would I allow someone to deliberately use hateful words against you. Google, for example, clearly says that it won’t allow hateful speech. Is there a difference in the definition of “hateful” ? Hardly a few years ago, it was common to find the “N” word being used freely. Now it is considered hateful. It took the African American population a lot of struggle to arrive at this stage. It shouldn’t have been like that. Someone pleading the “freedom of speech” right to openly be racist is not tolerated. Why is that? What makes intolerance towards racism different from intolerance towards religion?

[…] On Rights and Responsibilities, “Hate Speech,” and Google Paternalism, Jillian York blog post […]